'The Death of Woman Wang' Jonathan D. Spence (1978)

Here is a book that by insistently avoiding the formative places and events of history enables its readers to relate to it personally and emotionally, and to see it through an entirely different lens

Understanding history: Grand Narratives versus Personal Experiences

We can speak of history in terms of grand narratives - those events that shape the (geo)political and social (including cultural) realities of today - or in terms of personal, ‘lived and breathed’ experiences. Grand narratives are found in history textbooks, documentaries and other formal and academic sources. They are always impersonal, unrelatable, unlived: a top-down extraction, simplification, and reduction of countless personal experiences. These grand narratives may help to understand history intellectually, and as such have something to teach us about the causes and patterns of rise and fall that society is subject to, but these grand narratives cannot impress upon us the emotional, embodied experience of these events. History in grand narratives is an intellectual triumph, but an emotional failure. For this reason, trying to understand history only with reference to its ‘defining events’ will lead to a very incomplete, cerebral understanding.

Personal histories connect us to the human element of what transpired and remake history from being just a story of statistics and timelines (informing our minds), to a story of love and loss, vice and virtue, adventure and daring (inspiring our hearts). Unfortunately, personal histories hardly get preserved - they are found in the memories of individuals, in diaries, in court cases, obituaries, and other ephemeral sources. They may be included as passing examples in grand narrative perspectives, but they are never centre stage. (Intriguingly, personal histories are also reconstructed or invented in historical fiction - but then accuracy is of course out of the question).

When history is taught from both perspectives, then as a subject it takes on a freshness, a potency, a relevance and even a kind of playfulness that serves our hearts, not just our minds. Top-down perspectives are important, but if they are not grounded in personal histories, in grassroots, lived realities, then they are just another fact among many, failing to connect us more deeply to the meaning of each event.

A pioneer of Personal History

The title of Jonathan D. Spence’s book ‘The Death of Woman Wang’ already sets it apart as belonging to the marginal genre of personal history. We know by the first instead that this will be a kind of biographical history exploring the life (or lives) of certain people. Contrast this title to others such as ‘China after Mao’, ‘Japan, A Short History’, and ‘The Koreas: The Brith of Two Divided Nations’ - all these have a distinctly top-down ring to them and prepare the reader to expect a study of the development of economics, politics, and other social institutions within a given time span. For the latter titles individual stories are at the periphery and drawn on whenever they serve a certain point, for the former title (and other Spence’s books), the stories of individual people are at the centre, and more abstract topics, be they politics, economy or others, are only explored insofar as they shed light on the experiences of the people in discussion. Spence is a master of exploring history from the grassroots up and he does this in many of his other books.

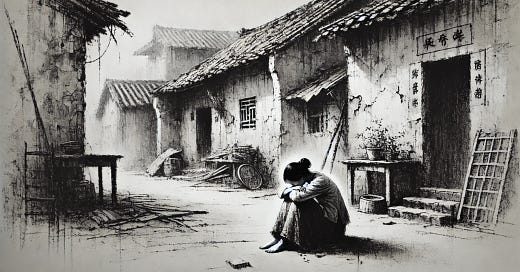

The Death of Woman Wang: a story of struggle

In the book ‘The Death of Woman Wang’ Spence explores the lives of a few individuals in a place that is - insofar as grand narratives are concerned - completely irrelevant. The struggles of certain individuals against famine, poverty, harsh weather, natural disasters, corrupt officials, unfair laws, and bandit invasions are documented with great detail and form the main theme of the book. Each character finds recourse in different ways - some by turning to criminal activity, others by suicide and some by simply grinding it out. In any case, Spence casts a very human light on it and makes it much easier to understand why certain people acted as they did. While reading, I felt very grateful of living in the time and place I am, which spares me of all these trials.

In any case, the book provides valuable insight on how people deal with different kinds of adversity not just practically, but also emotionally. Readers will find this book personally relevant and illuminating.